By Fardous Bahbouh, Researcher & Consultant on Labour Rights, Public Policy, and the Political Economy of the Translation Industry

Abstract

Despite being one of the world’s wealthiest nations, the UK continues to grapple with widespread poverty. In 2018, one-fifth of the population lived in poverty, with 1.5 million experiencing destitution (United Nations, 2019a). By 2024, poverty persists, disproportionately impacting women and ethnic minorities, including many who are working yet unable to make ends meet (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2024). Within this context, interpreters in the UK’s outsourced public service interpreting (PSI) sector face precarious working conditions, inadequate pay, and financial insecurity. These challenges are exacerbated by the power imbalances characteristic of outsourcing arrangements, despite the essential role of PSI in safeguarding human rights and ensuring equal access to public services.

PSI demands advanced linguistic and contextual knowledge, requiring interpreters to communicate accurately and reliably in legal, medical, and social service settings. They must also possess a thorough understanding of the systems and conventions within these contexts to facilitate effective communication and uphold high ethical standards. Their work often carries life-saving or life-changing implications for the individuals they serve.

This study adopts an intersectional critical realist framework to explore the lived experiences of interpreters and to analyse systemic and structural factors shaping their work, including neoliberal policies, power dynamics, and the lack of interpreters’ representation in decision-making processes. Conducted in two stages, the first phase involves an extensive literature review and quantitative data collection, surveying interpreters rates of pay, and working conditions. The second phase employs semi-structured interviews and document analysis, including a case study of court interpreting.

By addressing gaps in the academic literature, this study aims to contribute to a nuanced understanding of interpreters’ lived experiences within the UK’s outsourced PSI and the factors dictating their pay and working conditions. The study will then conclude by offering recommendations, ultimately contributing to more informed and effective policymaking.

Chapter One: Introduction and context

The United Kingdom (UK) is a diverse nation with a legal framework aimed at fostering equality and inclusion for all. The Human Rights Act 1998 incorporated the European Convention on Human Rights into the UK’s laws, making interpreting provision a legal requirement and integral part of the right to a fair trial (The Human Rights Act 1998). The Equality Act 2010 prohibits direct or indirect discrimination on the basis of protected characteristics such as age, religion, sex, sexual orientation and disability. It mandates that public organisations provide interpreting and translation services for individuals with limited English proficiency, ensuring equal access to public services (Equality Act 2010). These laws underscore the vital role interpreters play in safeguarding equality and human rights.

Public service interpreting (PSI) refers to interpreting that happens in the context of public services such as legal, medical and other social services such as housing, education, and welfare. It distinguishes the interpreting that takes place in such contexts from those of commercial, broadcast and conference interpreting (Wang & Pan, 2021). Other terms have also been used to refer to PSI including liaison interpreting, dialogue interpreting, and community interpreting (Wang & Pan, 2021). While PSI encompasses both spoken and sign language interpreting, this study will focus only on spoken interpreting between foreign languages and English. It will not address sign language interpreting or Welsh language interpreting, as these fields may involve distinct systemic differences. For example, sign language court interpreters often work in pairs, and some Welsh interpreters in Wales may be employed as in-house staff due to the high level of demand, given that Welsh is a national language.

PSI presents a distinctive context in the context of Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion (EDI). Although providing interpreting in a social services context is a state obligation, funded by taxpayers and mandated by legal frameworks, it is primarily outsourced to private translation companies, and in rare instances, to third-sector organizations. Additionally, PSI has critical impacts that could be life-shaping or life-changing for two social groups predominantly coming from marginalized backgrounds.

The first group is individuals with limited English proficiency who depend on interpreters to access public services. Quality issues in the provision of PSI have resulted in or contributed to miscarriages of justice and physical harm to patients. For example, insufficient language support in the criminal justice system has led to the wrongful arrests of crime victims, as reported by Victim Support and the Institute for Crime & Justice Policy Research (ICPR) (Dinisman et al., 2022). Additionally, inadequate interpreting support has contributed to cases of infant mortality and serious brain injuries (BBC File on 4, 2023). Women with limited or no English proficiency are also 25 times more likely to die during pregnancy and childbirth than those who speak fluent English (Rowntree, 2024). The persistence of these racial inequalities underscores the systemic and institutional racism embedded within public service provision in the UK (Feagin, 2013). While these critical issues provide important context for understanding the essential role of PSI, addressing them falls beyond the scope of this study.

The second impacted social group is the interpreters themselves, whose working conditions and compensation are often determined by the contract holder translation companies. Notably, a significant proportion of UK interpreters come from migrant backgrounds. For example, 95% of interpreters registered with the National Register for Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI) identify English as a second language. Furthermore, 64% of registered interpreters are women, while 36% are men (NRPSI, 2018).

Both academic literature and industry reports frequently characterize PSI by low pay, difficult working conditions, limited opportunities for career advancement, lack of health and safety considerations, and the absence of employment benefits such as paid leave and pensions (ATC & Nimdzi, 2023; ATC & PI4J, 2023; Dong & Turner, 2016; Drugan, 2020; Leminen & Hokkanen, 2024). However, a notable gap in the literature persists regarding critical issues, such as documenting the extent of interpreters’ low pay, examining how financial and job insecurity affect their well-being, and highlighting the lack of clarity surrounding responsibilities between translation companies and the public bodies commissioning interpreting services.

In outsourcing arrangements, translation companies are private businesses that act as intermediaries between public bodies requiring interpreting services and the interpreters. Translation companies control work allocation and rate setting, which can potentially lead to problematic power dynamics between interpreters and translation companies (Dong & Turner, 2016). Other terms such as agencies or language service providers are sometimes used to refer to these companies. This study uses the term translation companies to avoid potential confusion with the concept of agency, which refers to the capacity of individuals to act independently and make their own free choices to satisfy their goals and needs even under structural constraints, as defined by the English sociologist Anthony Giddens in his discussion on human agency, social structure, and the theory of structuration (2013). Additionally, the term language service providers encompasses a broader range of services, such as language teaching and voice-over in foreign languages.

The outsourcing of public services to private companies gained momentum in the UK during the late 20th century, spurred by the neoliberal policies of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (1979–1990). This shift fundamentally transformed the landscape of public sector employment (Harvey, 2005; Mazzucato & Collington, 2023; Standing, 2023). Outsourcing frequently led to reduced wages and benefits, heightened work intensity, and diminished job security. It also contributed to the rise of precarious employment, exacerbating social and economic inequalities while weakening the influence of trade unions (Bach, 2016; Healy, 2016; Heery & Simms, 2010; Kirton & Healy, 2013;).

Moreover, a 2023 BBC investigation in collaboration with the National Register of Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI) revealed that 10% of public service interpreters were unlikely to continue in the profession within the next 12 months due to inadequate remuneration (BBC File on 4, 2023). The BBC also reported on protests and strike actions by court interpreters and translators over freelance working conditions, with one interpreter stating that many of her peers were “pretty much on the poverty line” (BBC, 2024).

One particularly concerning trend, which appears to have received limited attention in interpreting literature and serves as a personal inspiration for my focus on working conditions and rates of pay, is the widespread practice among translation companies contracted for public service interpreting to operate “virtual call centres.” In these settings, interpreters are compensated solely for the minutes they actively spend interpreting, with no remuneration for waiting times, breaks, or personal necessities such as restroom use. While specific per-minute rates are not publicly disclosed, as a practicing interpreter, I am aware that current rates for phone interpreting range between 17 and 19 pence per minute. Given that assignments can be as brief as 15 minutes, interpreters often earn only £3–£4 per session, without any guarantee of additional work throughout the day or week. Considering the high level of skill required to be an interpreter (Wang & Pan, 2021), these rates seem strikingly low and potentially exploitative.

Economist Guy Standing (2023) highlights the problematic nature of precarious work, where workers endure unpaid waiting periods for brief, limited work opportunities, exacerbating financial instability and reducing workers’ control over how they spend their time. In the context of PSI, interpreters often face similar challenges, with long unpaid waiting times for a few minutes of paid work. Standing also warns that many precarious workers earn less than their essential financial needs, forcing them to rely on debt if they lack personal or family wealth, which leads to a vicious cycle of persistent poverty (Standing, 2011; 2023). The persistent poverty experienced by workers whose earnings do not cover basic living expenses is referred to as in-work poverty, which is becoming increasingly common worldwide, even in wealthy nations like the UK (Hick & Lanau, 2017; Wills & Linneker, 2014).

These issues are further compounded by the financial risks interpreters face when translation companies suddenly cease operations, leaving them unpaid for services already rendered. For example, interpreters were “left in limbo” and owed significant sums following the collapse of Debonair Languages as reported by Slator, a research and market intelligence organization specializing in the language industry (Slator, 2019). Debonair Languages was a subcontractor for TheBigWord, the sole holder of the MoJ interpreting contract. Similarly, in 2017, interpreters faced financial hardship when the translation company Pearl declared bankruptcy (Slator, 2017).

Despite these alarming reports, academic literature appears to lack a comprehensive analysis or documentation of the job and financial insecurities faced by interpreters, a gap this interdisciplinary research aims to address.

Furthermore, it is crucial to emphasise that financial insecurities and inequality could have profound implications for the health and well-being of workers and the society as a whole, as they may erode trust, contribute to the spread of diseases, and increase anxiety (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2010). For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic starkly revealed and exacerbated pre-existing socioeconomic disparities and insecurities across society, disproportionately impacting marginalised communities. Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups, for example, experienced significantly higher rates of infection and mortality, as highlighted by Public Health England (2020).

The pandemic also underscored the consequences of decades of austerity measures and chronic underfunding of social infrastructure, including healthcare, education, and public services which had a particularly severe impact on disadvantaged groups (Williams, 2021). Although public service interpreters were granted “key worker” status during the pandemic, there were few efforts to improve their pay rates or provide guidance for their safety (Slator, 2020).

Even though the pandemic served as a tangible example of the negative impact of inequalities and deprivations, highlighting the urgent need for policies that address structural inequalities to foster a healthier and more equal society, not much seems to have changed. In 2019, the United Nations reported that, despite being the world’s fifth-largest economy, one-fifth of the UK’s population – 14 million people – lived in poverty, with 1.5 million experiencing destitution in 2018 (United Nations, 2019a). Fast forward to 2024, and while the UK remains a wealthy nation, it continues to grapple with similarly high levels of poverty, which disproportionately affect women and individuals from minority ethnic backgrounds, many of whom are working yet still living in poverty (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2024).

To situate this study within the broader political context of the UK, it is important to note that a new Labour government came to power in July 2024, ending 14 years of Conservative rule, with promises to tackle poverty and reverse austerity measures that disproportionately affected the most vulnerable populations. The government also pledged to improve working conditions and address exploitative practices, such as zero-hour contracts (Labour Party, 2024).

However, despite these commitments, the MoJ issued a tender notice for interpreting and translation services in October 2024 (Bidstats, 2024). During her testimony at the House of Lords’ inquiry into court interpreting, the Minister of State for Courts and Legal Services, Sarah Sackman, insisted on allowing the market to dictate interpreters’ rates of pay (House of Lords, 2024b). This stance represents a clear departure from Labour’s campaign pledge to make work fairer for all (Labour Party, 2024). Many economists, including classical thinkers such as Adam Smith (1776) and John Stuart Mill (1849), acknowledge that markets are not always self-regulating and that government intervention is sometimes necessary to protect workers and ensure fair resource distribution, particularly in cases of monopolies.

Sackman was merely repeating the same platitudes about “fulfilment” and “fair rates” and insists on letting the market determine interpreters’ rates of pay. She appeared unaware of the contradictions in her evidence and completely oblivious to the reality that “racial and ethnic minorities are overrepresented in criminal justice enforcement and underrepresented within the institutions that adjudicate crime and punishment” (United Nations, 2019b).

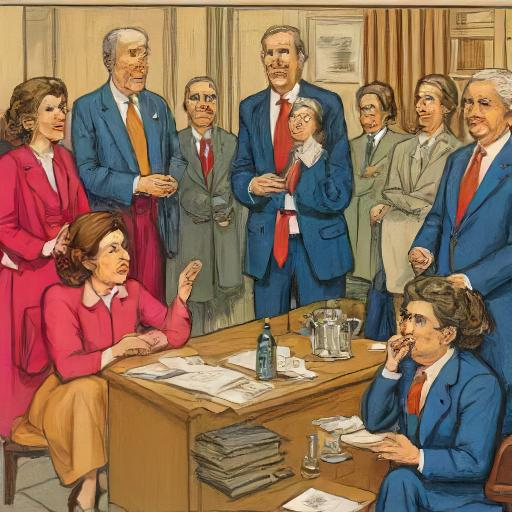

Furthermore, during the same House of Lords’ inquiry, a powerful visual example of the marginalisation of interpreters was seen on the 6th November 2024 (House of Lords, 2024c). In that session, non-interpreter CEOs of the three main organisations representing interpreters and translators – the Chartered Institute of Linguists (CIOL), the Institutes of Translation and Interpreting (ITI) and the National Register of public Service interpreters (NRPSI) – gave oral evidence to the committee. Surprisingly, interpreters themselves were relegated to the back of the room and were not given a chance to speak.

This study adopts an intersectional critical realist framework. Intersectionality helps to examine the intersecting identities of interpreters—such as gender, ethnicity, and class—and how these identities influence their experiences in the outsourced PSI sector (see Chapter 3). Critical realism (Roy Bhaskar, 2010) asserts that reality exists independently of our perceptions and understanding, though it is mediated through social structures, institutions, and individual actions. This perspective is particularly valuable for analysing how interpreters’ lived experiences are shaped not only by immediate, observable conditions but also by underlying systemic forces within the outsourced PSI sector (see Chapter 3). The study employs a mixed-methods approach (Bryman, 2016; Mellinger and Hanson, 2016; Saunders, 2019) and will be carried out in two stages. The first stage serves as an initial investigation, collecting large-scale quantitative data by means of a survey to capture the diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds of interpreters working in PSI.

Overall, this study aims to address gaps in the literature by documenting the diverse backgrounds of interpreters working in PSI and quantifying the various challenges they encounter. Additionally, it seeks to provide insights into the systemic factors that shape their work. By shedding light on these issues, the research aspires to develop a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the systemic challenges interpreters face, their broader implications, and to support efforts aimed at improving the well-being of interpreters.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.1 Public service interpreting and outsourcing

The importance of PSI was brought to the attention of the UK public and policymakers in the 1980s, following the case of Iqbal Begum, a Punjabi speaker who stood trial and was sentenced for the murder of her husband after she had been a victim of domestic violence. A few years after the trial, it was accidentally discovered that she did not understand the court proceedings, as she didn’t speak English or the language of the individual recruited as her ‘interpreter,’ who did not speak Punjabi. Begum was released on appeal. Tragically, she later took her own life (The Guardian, 2012; Townsley, 2008).

Another high-profile case was the tragic death of Victoria Climbié, a seven-year-old girl who arrived in the UK from the Ivory Coast, via France, in 1999, but died in 2000 as a result of severe abuse at the hands of her aunt and her aunt’s partner. Victoria’s death exposed significant failures in the child protection system in the UK, as her abusive aunt served as the language mediator between Victoria and social workers, health professionals, and police officers (Townsley, 2008; Williams, 2021).

Binhua Wang and Lihong Pan emphasise that PSI requires high specialisation to be able to interpret in the context of legal, medical and social services in addition to “the ability to communicate accurately and reliably in such contexts as the police station and the doctor’s consulting room requires a native speaker fluency that would be measured at postgraduate level in academic terms. Communication of that sort also demands a background understanding of the associated systems and conventions to make sense of the contexts” (2021, p.2).

However, PSI is frequently described in academic literature as involving low pay, difficult working conditions, limited career progression opportunities, and lack of employment benefits such as paid leave and pensions (Dong & Turner, 2016; Drugan, 2020; Leminen & Hokkanen, 2024) Furthermore, interpreters are often exposed to the risk of vicarious trauma when working in challenging environments, without receiving adequate psychological or well-being support (Chen, 2023; Määttä, 2015; Roziner & Shlesinger, 2010). While detailed academic research on the working conditions of interpreters in PSI remains limited, there is an almost complete absence of research addressing the financial insecurities interpreters experience and how such insecurities may negatively impact interpreters’ lives.

Two seminal studies by Jiqing Dong and Graham Turner (2016) and Joanna Drugan (2020) offer valuable insights into the problematic working conditions within the UK’s outsourced PSI system. Drugan presents original research conducted during the Transnational Organised Crime and Translation (TOCAT) project, which brought together academic researchers, contract-holders, interpreters, translators, language service providers, professional associations, and users of translation and interpreting services. It focuses on the novel and ethically challenging ‘translaborations’ in police settings. “Translaboration” refers to the evolving collaborations among various stakeholders involved in interpreting and translation in complex police environments. The study raises critical questions about interpreting quality and ethics in the management of large-scale public service delivery within framework agreements (Drugan, 2020, p.307).

Drugan’s analysis on complex collaboration in police interpreting shows that the introduction of outsourcing has altered traditional collaborations between interpreters and public service providers, adding complexity and making it more challenging to control the quality provided by private translation companies (2020). She notes that the outsourcing model disrupted longstanding direct relationships between interpreters and local police by introducing intermediary companies for booking interpreters from various geographical locations, imposing complex collaboration requirements and created new working conditions in which interpreters are expected to adhere to the intermediaries’ requirements, including the obligatory use of problematic booking apps and facing fines for lateness or inability to attend an assignment (2020). This underscores the absence of employee protection for interpreters. Not only do they not get paid sickness leave or time off for emergencies, but they are also subjected to fees for not showing up.

Drugan also explores a significant drawback in the current system relating to quality control and possibly problematic lack of internal capability of the Police to manage the outsourced interpreting provisions and control the quality of those provisions. Some of the police forces have outsourced the quality control of the already outsourced interpreting to the translation company The Language Shop. In her research, Drugan found that the same individuals working with the police as interpreters were being hired by The Language Shop to be quality assessors without any training or support regarding quality control (2020).

It is important to note that, on the 1 April 2021, the police introduced the Police Approved Interpreters and Translators Scheme (PAIT). This scheme requires police units to verify the vetting, qualifications, and experience of interpreters working through translation companies in law enforcement settings (UK Police, 2021). Additionally, some forces, such as the Metropolitan Police, set specific pay rates for interpreters, even when their services are contracted through translation companies (Metropolitan Police Services, 2022). While this is a positive practice that reduces or eliminates the risk of interpreters being exploited by translation companies, it reveals a devaluation of experience, as fixed rates mean that interpreters with decades of experience are paid the same as those with limited experience.

The other important study is by Dong and Turner who observed that the dynamics between interpreters and agencies lack sufficient research attention. They conducted ethnographic research to study the ergonomic impact of interpreting agencies on interpreters working in PSI, and to explore interpreters’ work experiences, professionalisation policies, and managerial practices (2016). They adopted the International Ergonomics Association (IEA)’s definition of Ergonomics, which is also known as ‘human factors’, as the scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of interactions among humans with other elements of a system (IEA, 2000). Their research was carried out through a case study at a national translation company providing PSI, which they gave the pseudonym Insight. Data collection was conducted over a number of months and included a questionnaire, field notes, meeting minutes, audio recordings of interpreters’ induction, research journal, in-house archival data, seminar discussions, and semi-structured interviews with five employees from the translation company, including a director and managers, and 15 interviews with freelance interpreters who take assignments not only from Insight but also from other agencies with a focus to give interpreters an opportunity to speak about this work experiences as “their voices are mostly unheard in the organisational discourse” (2016, p.9).

Their study identified several key findings regarding the adverse impact of agency practices on interpreters. There is a lack of formal grievance procedures to allow interpreters to voice their concerns, leading to a divergence in understandings of professionalism and an unequal distribution of power between interpreters and agency management. Interpreters often struggle with the procedural issues as translation companies have a tight control over work allocation, and the insistence on procedural adherence, create stress and operational challenges for interpreters. Interpreters experience inadequate health and safety measures, particularly during home visits or in potentially unsafe environments such as in prisons. The lack of formal training and risk assessment further exacerbates these issues (2016).

Furthermore, a main problem highlighted during interviews with interpreters during the study was interpreters’ hesitation to call agencies with queries for fear of being labelled as incompetent or losing future assignments. Also, interpreters often feel pressured to accept assignments, particularly when agency managers express urgency. Over half of the interviewed interpreters reported difficulty in refusing assignments due to fear of losing future work opportunities or being blacklisted. Interpreters reported problems with travel times, citing “spending more on waiting for the bus or stuck in traffic” or having to spend “three hours total on the way for only a 10-minute assignment” (2016, p.15). Interpreters also spoke about the unpredictable nature of their work and the lack of preparation time as they are usually not given advanced information about the nature and the topic of the assignments (Dong & Turner, 2016).

Dong and Turner concluded that translation companies’ managerial practices often undermine interpreters’ autonomy and their ability to perform effectively, leading to a professional identity crisis where interpreters feel more like low-paid, precarious workers than high-skilled professionals. Interpreters face ergonomic risks similar to those in other precarious employment sectors, such as mental stress, irregular working hours, and volatile work pace. These challenges are compounded by inadequate organisational support leading interpreters to withhold concerns or lose their ability to decline assignments out of fear of losing assignments or reputational damage. In turn, this highlights a stark disparity between the increasing number of regulatory measures in PSI and the declining working conditions for interpreters indicates a malfunction within the existing institutional system of PSI (Dong & Turner, 2016).

Both the above-mentioned studies offer invaluable insights into the challenges facing interpreters in PSI. However, there remains a notable lack of focus on pay rates and financial insecurity of public service interpreters. In his 2008 article, Brooke Townsley noted that interpreters working in Greater London for the courts or the police could expect remuneration ranging from £28 to £35 per hour, while those in the health or local government sectors commonly received £15 to £20 per hour (2008, p.7). In 2024, sixteen years on, media reports (BBC File on 4, 2023; Telegraph and Argus, 2019) and social media posts by interpreters and by the NRPSI indicate that these rates have mostly decreased, instead of increasing or adjusting for inflation, resulting in pay rates that sometimes fall below the minimum wage for skilled work that can have life-altering or even life-saving consequences for the end users of these services.

In the context of the lack of precise figures on low pay and financial insecurity faced by interpreters working in PSI, it is important to highlight concerns expressed by interpreting scholar Rebecca Tipton, who observes that “given the difficulties in sustaining a reliable income from interpreting (at least in Britain), it is not uncommon for interpreters to accept assignments across domains without fully understanding the consequences” (2017, p.5). This illustrates a negative consequence of the precarious nature of PSI, where financial difficulties might push interpreters to take on work beyond their areas of expertise.

Similarly, in her investigation of medical interpreting in Hong Kong, Ester Leung references the UK’s outsourced PSI system as “a dysfunctional” model, noting that it is “characterised by numerous complaints about the quality of interpreting services, low interpreter morale due to inadequate pay, and a lack of transparency” (2020, p.279). Both Tipton’s and Leung’s remarks further emphasize the detrimental impact of outsourcing on interpreters’ working conditions and the critical need to fill the data gap regarding financial insecurities for interpreters.

Furthermore, it is also crucial to point out that there could be a systematic problem that is not highlighted in interpreting academic literature. For example, the UK has had a National Minimum Wage enshrined in its laws since the National Minimum Wage Act of 1998. Notably, women, youth, and ethnic minorities are among the groups that have benefited the most from minimum wage regulations (Blau & Kahn, 2017; Lang & Spitzer, 2020; Neumark & Wascher, 2008). While the National Minimum Wage legislation has led to increased pay for many workers, it has not entirely eliminated the struggle some face in making ends meet, leading to the emergence of the living wage movement initiated in the UK in the early 2000s, spearheaded by grassroots organisations like the Living Wage Foundation and supported by trade unions, charities, and faith groups (Dickens & Manning, 2004; Wills & Linneker, 2014). A recent report by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimated that “a single person needs to earn £29,500 a year to reach a minimum acceptable standard of living in 2023. A couple with two children needs to earn £50,000 between them” (2023, p.2).

However, given that interpreters are often classified as sole traders—sometimes referred to as vendors—translation companies are not legally required to adhere to minimum wage requirements. In the context of the absence of detailed data regarding pay rates, as well as interpreters’ monthly and annual income, it is not possible to assess whether interpreters are able to earn a living wage.

Moreover, juxtaposing the concerns surrounding the low pay of public service interpreters – who primarily assist marginalised individuals – with the lucrative compensation received by conference interpreters working with influential figures and world leaders and considered as “the stars” of the translation industry (Dam & Zethsen, 2013) reveals a troubling devaluation of skills of interpreters working in PSI. Additionally, disparities in status are evident as conference interpreters are often viewed as high-status professionals, likened to medical doctors and university professors (Gentile, 2013), while public service interpreters are more frequently compared to nurses (Gentile, 2016). However, there is a lack of academic research on the competitiveness of well-paying conference, commercial and broadcast interpreting, and how many interpreters work across both public service and other sectors.

Another problematic systemic factor in the outsourcing arrangement is the lack of financial transparency regarding the distribution of public funds between translation companies’ profits and interpreter wages. For instance, the 2021 survey and report by the Association of Translation Companies (ATC) and Nimdzi on the UK language services industry revealed that translation companies self-reported gross margins of up to 77% for translation services and 67% for interpreting services. However, it remains unclear whether these figures pertain to public or private contracts (ATC & Nimdzi, 2021, p. 25). In 2023, ATC and Nimdzi reported that “the current size of the language services market in the UK is at between GBP 1.94 and 2.20 billion. This is up from the GBP 1.7 billion we estimated in 2021, and the figure cements the UK’s place as the largest single-country market for language services in Europe” (ATC & Nimdzi, 2023, p.8). This highlights a stark contrast between the industry’s financial growth and the ongoing struggles faced by interpreters within this market.

In addition to the lack of financial transparency, there are systemic issues regarding regulations, quality control, oversight, and accountability in outsourced PSI, with some sectors, such as the MoJ, incorporating limited quality control procedures. A troubling revelation emerged in a 2023 House of Lords debate, which revealed that the NHS in England has never monitored compliance with its guidance on interpreting services in primary healthcare (House of Lords, 2023). Given the critical role of accurate communication in healthcare settings and the potentially severe consequences of miscommunication, this represents a significant shortcoming.

The lack of financial transparency and systemic issues related to regulations, quality control, and oversight, in addition to low pay and challenging working conditions, have contributed to widespread dissatisfaction with the current outsourcing arrangements. In fact, there have been calls to end outsourcing altogether. For example, the 2014 independent review of the MoJ’s Language Services Framework found that 76% of UK-based interpreters and translators do not work with the MoJ’s outsourced interpreting services due to “issues around remuneration,” and 67% due to poor working conditions (2014, p.7). The review recommended that language services should not be outsourced to for-profit agencies, and that the MoJ should book language services directly with interpreters and translators (2014, p.58).

The limited research in the academic literature on PSI regarding the working conditions, challenges, and insecurities faced by interpreters stands in stark contrast to the extensive focus on other aspects, such as the necessary skills and competencies (Angelelli, 2006; Corsellis, 2008; Gile, 2009; Tipton & Furmanek, 2016; Wang & Pan, 2021), as well as training (Crezee, 2015; Hale & Campbell, 2003; Hale & Gonzalez, 2017; Mikkelson, 2013; Pöchhacker, 2004), quality assessment (Angelelli, 2007; Hale et al., 2009; Pöchhacker, 2001), and the special requirements for specialised fields such as medical, legal, and social services interpreting (Crezee, 2015; Hale, 2020; Pöllabauer, 2004; Sossin & Yetnikoff, 2007; Tipton & Furmanek, 2016).

Additionally, the academic literature addresses the use of appropriate technologies for PSI (Braun, 2013; Roziner & Shlesinger, 2010; Sossin & Yetnikoff, 2007), the ethical duties and responsibilities of interpreters (Drugan, 2017; Leminen & Hokkanen, 2024; Määttä, 2015; Phelan et al., 2020; Raído et al., 2020).

2.2 Insights from Translation Studies

Given that the field of translation studies is more established and highly researched, and interpreting is sometimes considered “a form of Translation” (Pöchhacker, 2022, p.148), this section references important insights from translation studies. Joss Moorkens highlighted that similarly to interpreters, translators working in public services in the UK face significant challenges and job insecurity due to neoliberal policies and outsourcing practices. Translators are increasingly pressured to meet unrealistic work demands, be available round-the-clock, and cope with the insecurity of precarious work. Meanwhile, translation companies benefit from outsourcing arrangements, especially in avoiding regulations such as minimum pay (2017; 2020). Therefore, the current outsourced arrangement of public service interpreting and translation, presents interpreters and translators alike with low pay rates, inadequate support, unfavourable working conditions, and diminished prestige.

Joseph Lambert and Callum Walker delve into the complexities faced by freelance translators working mainly in the private sector. Acknowledging the precarious nature of translators’ work, they discuss the impact of technological advancements, the emergence of platform economies or Uberisation of the industry, and the increasing dominance of super large translation companies, who often dictate lower rates, leaving freelancers with the dilemma of accepting lower-paying work from translation companies or pursuing higher-paying but less stable direct-client projects (2022).

Lambert and Walker also mention an important issue regarding translation qualifications that translators with postgraduate degrees in translation marginally command higher rates than those without such credentials (2022, p.9). Chan (2010) reveals that while such certifications may enhance the professional image of translation companies and streamline their hiring process, the financial rewards for translators are minimal. Lambert and Walker highlight the need for open dialogue on pay rates to enhance the industry as survey data often highlight translators’ rates as a primary ethical concern (2022).

Similarly, in their 2024 article, Lambert and Walker continue their pioneering work, highlighting various challenges faced by translators, including disruptive changes in workflows, burnout, isolation, and persistent concerns about status, pay rates, and well-being. Despite these obstacles, the authors reference Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to suggest that some translators can still achieve self-actualization through their work. In their discussion, they state that “for most translators, in the UK at least, basic needs are likely met,” without specifying whether these basic needs are met through income from translation work or reliance on state benefits (2024, p.79).

However, it could be argued that such optimism in expecting self-actualization under intense insecurities risks overlooking how merely meeting basic needs might negatively impact translators by diminishing their sense of self-worth and agency. Moreover, translators may feel increasingly insecure about the future of their careers due to technological advancements, such as significant improvements in machine translation and the rise of generative AI in recent years.

Furthermore, reducing discussions of translators’ and interpreters’ financial security to mere subsistence is potentially problematic, as it might contribute to normalising the widespread devaluation of the required skills and expertise for translation, including mastering two or more languages, acquiring subject-specific knowledge, and developing essential communication skills. It also disregards the significant time and financial investments in education, including, for some, obtaining translation degrees and diplomas.

Furthermore, Lambert and Walker attribute the fact that many translators keep working in the industry despite the significant challenges to job satisfaction, a love for the creativity their work requires and an appreciation for the flexibility it offers (2024). However, the authors do not address the possibility that translators might be continuing to work in these harsh conditions due to the lack of viable alternatives, especially for marginalised groups in the UK, who might be facing structural inequalities and intersectional barriers (Huws, 2014; Warren & Lyonette, 2015). For example, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) estimated that by the end of 2022 there were around 3.9 million people in insecure employment including those on zero-hour contracts, low-paid jobs, and temporary agency work (2023), a significant increase from the TUC 2018 estimate of 3.2 million people (2018).

It is also important to emphasise that even when jobs offer fulfilment, financial insecurity and the potential for exploitation remain significant concerns that require attention. The 2017 Understanding and Measuring Job Quality report by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) points out that some jobs may be “objectively poor but perceived to be good,” citing the example of low-skill and low-wage roles like classroom assistants. These roles, while providing meaningful work, often come with inadequate pay and limited opportunities for career progression. The CIPD report quotes a classroom assistant stating, ‘I and my fellow colleagues are being exploited, but we love our jobs’ (CIPD, 2017, p.19).

Furthermore, given the high cost of living in the UK compared to other countries, the rise of translation platforms that allow translators to bid for work globally, places UK-based translators at a significant disadvantage in the global market, complicating their ability to compete and meet basic needs in an industry characterized by low barriers to entry. For example, a recent study (Fırat et al., 2024) examines whether the labour conditions of translators based in Turkey using platforms to obtain translation jobs comply with the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) standards for decent work. The authors identified significant challenges such as insufficient earnings, poor work-life balance, and a lack of social security, emphasising the necessity for better labour protections and fairer working conditions. The study concluded that translation platforms intensify precarious work conditions, fundamentally affecting the profession’s sustainability.

2.3 EDI challenges

This section examines scholarly insights on the concepts of EDI and explores how these principles can be applied to the context of outsourced PSI. The concepts equality, diversity and inclusion are interconnected yet distinct, and their interpretations vary across disciplines, contexts, institutions, and countries. This research will adopt the following definitions by Aleksandra Thomson and Rachael Gooberman-Hill from their 2024 book Nurturing Equality, Diversity and Inclusion:

Equality refers to “the provision of fair and same treatment to everyone.” Diversity is defined as “the presence of wide ranges of people representing categories of difference in relation to gender, age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, (dis)ability, culture, nationality, religion, socio-economic background, class, education, neurodiversity, among further aspects of difference.” Inclusion, on the other hand, refers to “the creation of welcoming and respectful environments in which difference is celebrated, and everyone feels valued and wanted” (Thomson & Gooberman-Hill, 2024, pp.7-30).

Thomson and Gooberman-Hill also discuss the term equity, which is sometimes used instead of equality. Equity highlights the importance of recognizing the challenges that disadvantage individuals may face, including factors related to personal characteristics and the social structures and systems in which they live. However, the authors caution that the concept of equity may risk diverting attention away from regulation and legislation. Rather than addressing and resolving systemic issues that perpetuate inequality, equity approaches can lead to differentiating between individuals based on their presumed needs. (Thomson & Gooberman-Hill, 2024, pp.7-30). For these reasons, this research will consistently use the term equality.

However, it crucial to highlight the contrast between the positive rhetoric surrounding EDI and the harsh realities experienced by interpreters working in PSI (see section 2.1). Sara Ahmed (2012) critiques the positivity often linked to EDI, arguing that it risks obscuring the persistent struggles of marginalised groups to achieve equal rights, fair pay, and opportunities. These ongoing struggles for a more equal distribution of resources, opportunities, and power intersect with postcolonial calls to decolonise the narratives of marginalised groups through representation and the creation of knowledge that challenges dominant frameworks (Collins, 2019; Gilroy, 2004; Healy, 2016; Healy & Oikelome, 2013; Mills, 2000; Özbilgin et al., 2011).

Moreover, in her book Justice and the Politics of Difference (1990) Iris Marion Young examines critical aspects of oppression such as exploitation and marginalization. Young defines exploitation as a form of oppression that “occurs through a steady process of the transfer of the results of the labour of one social group to benefit another” (1990, p.14). Structural and institutional mechanisms maintain a power imbalance, enabling the dominant group to extract value from the subordinate group. This dynamic is evident in outsourced PSI, where translation companies pay low rates while profiting significantly from interpreters’ labour.

Marginalization, which Young ranked as ‘perhaps the most dangerous form of oppression’, occurs when a group of people are subjecting to harsh material deprivation and excluded from meaningful participation in politics and social life (1990, p.18).

Similarly, Hannah Arendt’s The Human Condition (1958) also highlights how individuals engaged in constant labour to meet basic needs are excluded from participating in the public sphere, where meaningful political action and collective freedom occur. In the outsourced PSI sector, financial insecurity and potential exploitative conditions not only limit their capacity to advocate for better pay and conditions, but could also hinder their broader engagement in civic life and democratic processes. Despite being skilled and educated professionals, interpreters have only made some small attempts to organise. They have yet to organise large-scale, effective collective action to challenge the inequalities that perpetuate their precarious working conditions.

2.4 Keynesian vs. neoliberal economics

To fully understand the multifaceted factors shaping interpreters’ experiences in the outsourced PSI sector, it is essential to examine how economic theories have shaped public policies and, in turn, influenced labour markets and public services. The interplay between government roles, outsourcing mechanisms, power dynamics, and neoliberal policies forms the backdrop against which PSI operates. This section explores two key schools of thought in economic theory – Keynesianism and neoliberalism – and their profound implications for public service provision, labour conditions, and interpreters working within outsourced arrangements.

Keynesian economics, rooted in the ideas of John Maynard Keynes, emphasises the critical role of government intervention in stabilising economies and promoting employment. Keynesian economics were formulated in response to the Great Depression of the 1930s, revolving around the theory that during economic downturns and recessions, as private sector usually restrict its spending, resulting in increased unemployment and decreased investments, governments should actively intervene in the economy through fiscal policy—specifically, by increasing public spending and reducing taxes to stimulate demand and create jobs. Keynes famously stated, “The boom, not the slump, is the right time for austerity at the Treasury” (1937, p.390). He also emphasised the importance of social welfare programmes and labour protections as means to ensure economic stability and social justice.

During the post-World War II period, many Western countries adopted Keynesian policies, and established welfare states, public healthcare, and education systems, as well as robust labour laws contributing to decades of economic growth, rising wages, improved living standards, and low unemployment (Galbraith, 1987; Krugman, 2009; Skidelsky, 1992). Economic historian Tony Judt argues, “The Keynesian welfare state was instrumental in ensuring a fairer distribution of wealth and in mitigating the social inequalities that had led to political instability in the past” (Judt, 2005, p.314).

On the other hand, neoliberal economics, shaped by the ideas of Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, primarily advocates for free-market principles and minimal government interference, and has led to the widespread outsourcing of public services to private companies. In his book The Road to Serfdom (1944), Hayek argued that government intervention in the economy inevitably leads to a loss of individual freedoms and paves the way for totalitarianism. Hayek believed that only free markets could provide the necessary conditions for individual liberty and economic efficiency. Similarly, Milton Friedman, argued that “the great advances of civilisation […] have never come from centralised government” (Friedman, 1962, p.3).

Neoliberal economics gained prominence in the late 20th century, particularly during the 1980s under the leadership of figures like Margaret Thatcher (1979-1990) in the UK and Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) in the US who believed that free markets were the most efficient means of allocating resources, generating wealth, and promoting individual freedom. Neoliberalism advocates for minimal government intervention, deregulation, tax cuts, and the privatisation of public services. The outsourcing of public services is a clear example of how neoliberal policies have reshaped labour markets.

However, outsourced workers often endure poor working conditions, low pay, and limited opportunities for career advancement (Bach, 2016; Healy, 2016; Heery & Simms, 2010; Kirton & Healy, 2013). David Harvey argues that neoliberalism’s emphasis on market dynamics and cost reduction has led to the erosion of stable employment and the rise of precarious work. This shift disproportionately impacts disadvantaged groups, including women, minorities, and low-skilled workers, thereby exacerbating social inequalities and economic insecurity (Harvey, 2005).

Economists Mariana Mazzucato and Rosie Collington argue that outsourcing public services could even force workers to rely on state benefits due to insufficient earnings from companies holding public service contracts. This outcome directly contradicts the original justification for outsourcing, which was to reduce costs for the state (Mazzucato & Collington, 2023, pp.68-97). Additionally, Mazzucato and Collington assert that outsourcing reduces service quality and weaken public institutions by eroding their capacity to effectively manage and monitor contracts or provide services in-house. Consequently, this fosters an unhealthy dependency on profit-oriented companies, undermining the long-term provision of adequate public services (Mazzucato & Collington, 2023, pp.68-97).

The adverse effects of outsourcing policies are evident in numerous high-profile failures, characterized by substandard service delivery, lack of transparency, and ethical concerns surrounding the prioritization of profit over public welfare (Andersson et al., 2019; Mazzucato & Collington, 2023). For instance, the collapse of Carillion in 2018 and deficiencies in private prison rehabilitation programs underscore the risks of over-reliance on private contractors for essential public services (Andersson et al., 2019; Mazzucato & Collington, 2023). Similarly, Kevin Albertson, Mary Corcoran, and Jake Phillips note that in the criminal justice context, “the ascendancy of market imaginaries is such that their influence on policing, prisons, probation, legal services, and the courts—let alone numerous ancillary services, from prisoner transport to interpretation services—is seemingly irreversible” (2020, p.1).

A particularly striking example occurred during the London Olympics when private security firm G4S failed to recruit and train sufficient personnel, requiring the deployment of 18,200 army troops on short notice to ensure security (British Forces Broadcasting Service, 2017). However, in for individuals with limited English proficiency, there is no equivalent “army of linguists” to fill critical gaps when interpreting services fall short. This underscores the urgency of improving provisions for public service interpreting (PSI) to avoid further marginalizing vulnerable populations and compromising essential services.

The current PSI outsourcing arrangement has led to significant risks for people with limited English proficiency due to insufficient or inadequate interpreting provisions across public sectors, impacting healthcare, criminal justice, and overall public services (BBC File on 4, 2023; Dinisman et al., 2022; Rowntree, 2024). It also led to the persistence of the practice of language brokering where family members, friends, or even children serve as interpreters. Research has shown the potential adverse effects of language brokering, for violating the privacy of the individual seeking public services and exposing children to sensitive, stressful, and confidential topics that may not be age-appropriate (Angelelli, 2010; Garcia-Sanchez, 2018; Guan et al., 2020; Iqbal & Crafter, 2022; Valdés et al., 2003). Furthermore, language brokering often disadvantages people with limited English proficiency and violates their right to dignity and privacy, particularly in sensitive situations such as medical consultations (Maternal & Child Enquiries, 2011).

Chapter Three: Theoretical framework

This section discusses the intersectional critical realist theoretical framework that will be applied to investigate interpreters’ experiences in the outsourced PSI sector, as well as the systemic factors and power structures shaping these experiences. For intersectionality, the framework draws on the work of three key scholars. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989) conceptualization of intersectionality is foundational, emphasizing the compounded racial and gender inequalities faced by Black women. Crenshaw advocates for legal protections that recognize Black women as a distinct group vulnerable to discrimination due to the intersecting nature of their race and gender.

The framework also incorporates Joan Acker’s theory of “inequality regimes” (2006), which examines how organizations perpetuate inequalities based on class, race, and gender. Additionally, the framework draws on Patricia Hill Collins’s work on intersectionality as critical social theory, emphasizing the role of knowledge creation in resisting systems of political domination. Collins focuses on the intersecting frameworks of race, class, gender, and other identity markers, which have been shaped and reinforced over time (Collins, 2021).

Collins critiques traditional disciplinary approaches for their “conceptual blind spots,” arguing that they often lead to narrow analyses of power relations and overlook the lived experiences of marginalized groups (Collins, 2021, p.291). Thus, intersectionality offers a broader framework for intellectual and political engagement across differences. By integrating both top-down and bottom-up perspectives, intersectionality encourages diverse communities to generate new questions and solutions aimed at dismantling power structures rather than merely explaining them.

Collins outlines six central constructs in intersectionality: relationality, power, social inequality, social context, complexity, and social justice. She also identifies four guiding principles: the interdependence of markers of power such as race, gender, class, sexuality, nationality, ethnicity, ability and age; the production of interdependent social inequalities through intersecting power relations; the impact of individuals’ social locations on their perspectives; and the need for intersectional analysis to address social issues at multiple levels (Collins, 2021, p.295). Ultimately, Collins positions intersectionality as both a critical analytical tool and an integral component of resistance against intersecting systems of power.

To further understand these systems of power, the theoretical framework of this study will also adopt a critical realist perspective, building on the foundational work of Roy Bhaskar (2010). Critical realism asserts that reality exists independently of our perceptions, but our understanding of it is always mediated by social structures, institutions, and individual actions. Bhaskar’s critical realism theory of the social sciences evolved from his work on scientific critical realism, positing that the social world operates according to causal mechanisms and structural factors even though our capacity to comprehend them is filtered through individual interaction with societal systems. This perspective is particularly valuable for analysing the multifaceted realities interpreters face in the outsourced PSI sector, where systemic forces and individual experiences converge.

From a critical realist viewpoint, interpreters’ lived experiences are not merely the result of immediate, observable conditions—such as low pay, precarious contracts, or inadequate support. These experiences are also deeply influenced by underlying systemic forces, including the economic logic of outsourcing and new liberalism, government policies on public services procurement, problematic power dynamic between translation companies and interpreters, the lack of interpreters’ representation in the decision-making processes, and the broader socio-political context that devalues certain forms of labour. By situating interpreters’ challenges within this layered understanding of reality, critical realism allows for an exploration of not only what happens on the surface but also why these conditions persist and how they are reinforced by invisible structures and mechanisms. This approach is crucial for identifying pathways towards meaningful change that address the underlying structural problems.

Bhaskar’s critical realism distinguishes between three domains of knowledge: the empirical, the actual, and the real. The empirical refers to what we can directly observe or experience, such as interpreters’ reported dissatisfaction with pay or working conditions. The actual encompasses events and processes that occur, whether or not they are observed—such as consultations the public bodies conduct before launching tendering processes. These consultations affect interpreters, but may remain unnoticed by the public. Finally, the real consists of the underlying structures, such as market-driven policies or power dynamics within the PSI sector, that generate these events and experiences.

Similar to Collins’ intersectionality as critical social theory (2021), Bhaskar’s critical realism (2010) emphasises the role of knowledge in understanding power structures and driving social change. By gathering evidence and analysing the systemic and structural factors affecting interpreters, this study aims to contribute to a body of knowledge that could ultimately help drive meaningful reform in the sector.

By employing intersectionality and critical realism, this study seeks to uncover both the visible and hidden forces shaping interpreters’ experiences, as well as the systemic inequalities embedded within the structure of outsourced public services. This theoretical framework facilitates a multi-layered analysis that not only documents interpreters’ experiences but also examines the constraints imposed by outsourcing models while delving deeper into power dynamics.

Positionality and reflectivity statement:

I am a UK-based freelance interpreter and translator. I am motivated to conduct this research by my belief in the importance of social justice and my desire to critically analyse some of the complex ethical dilemmas in our world.

Personally, I have chosen not to work in outsourced public service interpreting to translation companies due to the low pay rates, which I view as exploitative. Instead, as a way to give back to my community, I have volunteered as an unpaid interpreter and English teacher with various charities, including Citizens UK, Safe Passage International, and Ahlan Wa Sahlan – Welcome.

Throughout the research, I will reflect on how my background and positionality may influence the study. Frequently, I will be reflecting on potential biases to increase transparency, enhance the reliability of my findings, and maintain ethical integrity, as suggested by Roni Berger (2015).

Furthermore, I will utilise my own experience and awareness of potential sensitivities and implied meanings of some of the terminology to produce a suitable narrative that reflects the interpreters’ views. I will be mindful and sensitive in communicating with the study participants and in forming my questions to avoid leading the participants on to reinforce or amplify my own assumptions.

Conclusion

This report has outlined the structure and progression of my research thus far. It began by providing an introduction and context to PSI and the legal framework mandating interpreting provision in social services contexts, before delving into the problems associated with outsourcing arrangements and their adverse implications for interpreters. Key terminology was defined, alongside a discussion of the primary contribution my thesis will make to the field.

The literature review followed, critically examining both interpreting and translation literature and addressing challenges related to equality, diversity and inclusion, before incorporating insights from economic theories to build a framework for exploring the interplay between intersecting inequalities, outsourcing mechanisms, power dynamics, government roles and the effects of neoliberal policies contributing to the growing prevalence of precarious work. These insights were organized by thematic subsections, highlighting gaps in current knowledge and contextualizing the importance of exploring interpreters’ experiences within the outsourced PSI arrangements.

The theoretical framework, though still in development, was briefly discussed, focusing on intersectionality (Acker, 2006; Collins, 2021; Crenshaw, 1989) and critical realist (Bhaskar, 2010). These theoretical foundations will guide further analysis as the research progresses.

Overall, this report reflects the progress made so far and sets the stage for the next steps in completing the research, with ongoing refinement of the theoretical framework and further data collection and analysis.

Bibliography

Acker, J. 2006. Inequality regimes: Gender, class, and race in organizations. Gender & Society. 20(4), pp.441–464.

Ahmed, S. 2012. On being included: racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham; London: Duke University Press.

Albertson, K. Corcoran, M. Phillips, J. eds. 2020. Marketisation and privatisation in criminal justice. Bristol: University of Bristol.

Anon 2017. Ministry of Justice. Government Response to the Lammy Review on the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the Criminal Justice System. Accessed 9 January 2025. https://parlipapers-proquest-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/parlipapers/result/pqpdocumentview?accountid=14664&groupid=95672&pgId=d054b240-f91b-4b2f-9598-3c502e995300

Andersson, F., Jordahl, H. and Josephson, J. 2019. Outsourcing public services: contractibility, cost, and quality. CESifo Economic Studies. 65(4), pp.349–372.

Angelelli. C.V. 2006. Validating professional standards and codes: challenges and opportunities. Interpreting: international journal of research and practice in interpreting. 8(2), pp.175–193.

Angelelli, C.V. 2007. Assessing medical interpreters: the language and interpreting testing project. Translator. 13(1), pp.63–82.

Angelelli, C. V. 2010. A professional ideology in the making: bilingual youngsters interpreting for their communities and the notion of (no) choice. Translation and Interpreting Studies. 5(1), pp.94-108.

Arendt, H. 1958. The Human Condition. University of Chicago Press.

ATC, and Nimdzi. 2019. UK language services industry survey and report. Accessed 24 November 2023 https://atc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/ATC-UK-Survey-and-Report.pdf

ATC, and Nimdzi. 2021. UK language services industry survey and report. Accessed 24 November 2023.https://atc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/ATC-UK-Survey-and-Report_2021.pdf

ATC, and Nimdzi. 2023. UK language services industry survey and report. Accessed 24 November 2023. https://atc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/ATC-UK-Language-Services-Industry-Survey-and-Report-2023-1.pdf

ATC and PI4J. 2023. Working together: recommendations for tackling the immediate issues facing procurement and provision of language services for the public sector. Accessed 27 July 2024. https://www.nrpsi.org.uk/downloads/231120-UK-Language-Services-for-the-Public-Sector-Working-Together.pdf

Bach, S. 2016. Shrinking the state or the big society? Public service employment relations in an era of austerity. Industrial Relations Journal. 47(1), pp.2-17.

BBC File on 4. 2023. Lost in Translation. Accessed 21 November 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m001sm8z

BBC. 2024. Secret papers reveal Post Office knew its court defence was false. Accessed 3 April 2024. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-68663750#:~:text=A%20draft%20report%20uncovered%20by,IT%20system%20or%20remote%20tampering

Beinchet, A. and Taibi, M. 2024. Community Translation and Interpreting Under Neoliberal Agendas: The Cases of Australia and Canada. In: Jalalian Daghigh, A. and Shuttleworth, M. eds. Translation and neoliberalism. New frontiers in translation studies. Springer: Cham, pp.99-118. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-73830-2_5

Benhabib, S. 1996. Democracy and difference: contesting the boundaries of the political. Princeton University Press.

Berger, R. 20015. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative research: QR. 15(2), pp.219-234.

Berlin, I. 2004. Liberty. Hardy, H. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beauvoir, S. 1949. The Second Sex. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Beveridge, W. 1942. Social insurance and allied services. Parliamentary Archives, BBK/D/495. Accessed 27 July 2024. https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/coll-9-health1/coll-9-health/

Bhambra, G.K. 2007. Rethinking modernity: postcolonialism and the sociological imagination. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Bhaskar, R. 2010. Reclaiming reality: a critical introduction to contemporary philosophy. London: Verso.

Bidstats. 2024. A tender notice by Ministry of Justice: the provision of language services. Accessed 2 December 2024. https://bidstats.uk/tenders/2024/W40/831914148

Blau, F.D. and Kahn, L.M. 2017. The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of economic literature. 55(3), pp.789–865.

Braun, S. 2013. Keep your distance? Remote interpreting in legal proceedings: a critical assessment of a growing practice. Interpreting: international journal of research and practice in interpreting. 15(2), pp.200–228.

British Forces Broadcasting Service, 2017. Troops on the streets: a history. Accessed 3 April 2024. https://www.forces.net/news/troops-streets-history#:~:text=The%20Armed%20Forces%20made%20up,troops%20deployed%20to%20provide%20security.

Bryman, A. 2016. Social research methods. Fifth edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Canovan, M. 1992. Hannah Arendt: a Reinterpretation of Her Political Thought. Cambridge University Press.

Cappelli, P. 2012. Why good people can’t get jobs: the skills gap and what companies can do about it. Wharton Digital Press.

CIPD. 2017. Understanding and measuring job quality. Accessed 16 October 2024. https://www.cipd.org/globalassets/media/knowledge/knowledge-hub/reports/understanding-and-measuring-job-quality-3_tcm18-33193.pdf

CIPD. 2018. Indicators of Job Quality. Accessed 16 October 2024. https://www.cipd.org/globalassets/media/knowledge/knowledge-hub/reports/understanding-and-measuring-job-quality-2_tcm18-36524.pdf

Chan, A. 2010. Perceived benefits of translator certification to stakeholders in the translation profession: a survey of vendor managers. Across Languages and Cultures. 11(1), pp.93-113.

Chen, T. 2023. The interplay between psychological well-being, stress, and burnout: Implications for translators and interpreters. Heliyon. 9(8). Accessed 3 December 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18589

Claeys, G. 2022. John Stuart Mill: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cleland, J., MacLeod, A. and Ellaway, R.H. 2021. The curious case of case study research. Medical education. 55(10), pp.1131–1141.

Collins, P. H. and Bilge, S. 2016. Intersectionality – key concepts. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Collins, P. H. 2019. Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Durham: Duke University Press.

Collins, P.H., Da Silva, E., Ergun, E. Furseth, I., Bond, K., and Mart ́ınez-Palacios, J. 2021. Critical Exchange: Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Contemporary Political Theory. 20(3), pp.690–725.

Corsellis, A. 2008. Public service interpreting: the first steps. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Crenshaw, K. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum. 1989(1), 139-167.

Crezee, I. 2013. Introduction to healthcare for interpreters and translators. John Benjamins.

Crezee, I. 2015. Semi-authentic practices for student health interpreters. The international journal of translation and interpreting research. 7(3), pp.50–62.

Dam, H., and Zethsen, K. K. 2013. Conference interpreters – the stars of the translation profession? A study of the occupational status of Danish EU interpreters as compared to Danish EU translators.” Interpreting. 15(2), pp.229-259.

Darroch, E. and Raymond, D. 2016. Interpreters’ experiences of transferential dynamics, vicarious traumatisation, and their need for support and supervision: a systematic literature review. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology. 4(2), pp.166–190.

Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. 2023. Critical race Theory: an introduction Fourth edition. New York: New York University Press.

Dickens, R. and Manning, A. 2004. Has the national minimum wage reduced UK wage inequality? Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A, Statistics in society. 167(4), pp.613–626.

Dinisman, T., Moroz, A., Anastassiou, A. and Lynall, A. 2022. Language barriers in the criminal justice system. Accessed 30 March 2024. https://www.victimsupport.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Language-barriers-in-cjs_The-experience-of-victims-and-witnesses-who-speak-ESL.pdf

Dong, J. and Turner, G. 2016. The ergonomic impact of agencies in the dynamic system of interpreting provision: An ethnographic study of backstage influences on interpreter performance. Translation Spaces. 5(1), pp.97–123.

Drugan, J. 2017. Ethics and social responsibility in practice: interpreters and translators engaging with and beyond the professions. Translator. 23(2), pp.126-142.

Drugan, J. 2018. Ethics. In: Rawling, P. and Wilson, P. eds. The Routledge handbook of translation and philosophy. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon; Routledge, pp.243-255.

Drugan, J. 2020. Complex collaborations: interpreting and translating for the UK police.” Target. 32(2), pp.307-326.

Edwards, P., O’Mahoney, J. and Vincent, S. 2014. Studying organizations using critical realism: A practical guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Equality Act 2010. Accessed 9 December 2023. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

Eurofound. 2012. Trends in job quality in Europe. Accessed 20 October 2024. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2012/trends-job-quality-europe

Eurofound. 2017. 6th European working conditions survey. Accessed 20 October 2024. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/b4f8d4a5-b540-11e7-837e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Feagin, J. 2013. Systemic Racism: A Theory of Oppression. Taylor & Francis.

Feldman, D. C. 1996. The nature, antecedents and consequences of underemployment. Journal of Management. 22(3), pp.385-407.

Financial Times. 2011. Capita widens remit with £7.5m purchase of ALS. Accessed 3 April 2024. https://www.ft.com/content/21108e70-2d6f-11e1-b985-00144feabdc0

Firat, G., Gough, J., and Moorkens, J. 2024. Translators in the platform economy: A decent work perspective. Perspectives: Studies in Translation Theory and Practice. 32(3), pp.422–440.

Fraser, N. 2009. Scales of justice: reimagining political space in a globalizing world. New York: Columbia University Press.

Fraser, N. 2022. Cannibal capitalism: how our system is devouring democracy, care, and the planet – and what we can do about it. London: Verso.

Friedman, M. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. University of Chicago Press.

Galbraith, J.K. 1987. The affluent society. Fourth edition with a new introduction. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Garcia-Sanchez, I. 2018. Children as Interactional Brokers of Care. Annual Review of Anthropology. 47 (1), p.167-184.

Gentile, P. 2013. The Status of Conference Interpreters: A Global Survey into the Profession. Rivista internazionale di tecnica della traduzione. 15(1), pp.63-82.

Gentile, P. 2016. The Professional Status of Public Service Interpreters. A Comparison with Nurses. FITISPOS International Journal. 3(1), pp.174-183.

Giddens, A. 2013. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gile, D. 2009. Basic concepts and models for interpreter and translator training. Amsterdam; John Benjamins.

Gilroy, P. 2004. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

Grigoroglou, C., Walshe, K., Kontopantelis, E., Ferguson, J., Stringer, G., Ashcroft, D. M. and Allen, T. 2022. Locum doctor use in English general practice: analysis of routinely collected workforce data 2017-2020. Br J Gen Pract. 72(715), pp.108-117.

Guan, S.-S. A., Weisskirch, R. and Lazarevic, V. 2020. Context and Timing Matter: Language Brokering, Stress, and Physical Health. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 22(6), pp.1248-1254.

Habermas, J. 1989. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT Press.

Hale, S. 2007. Community Interpreting. Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hale, S. 2011. The positive side of community interpreting: An Australian case study. Interpreting. 13(2), pp.234–248.

Hale, S. 2020. Court interpreting. The need to raise the bar: court interpreters as specialized experts. In: Coulthard, M., May, A. and Sousa-Silva, R. eds. The Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics. London & New York: Routledge, pp.485-501.

Hale, S. and Campbell, S. 2003. Translation and Interpreting Assessment in the Context of Educational Measurement. In: Anderman, G.M. and Rogers, M. eds. Translation today: trends and perspectives. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp.205-224.

Hale, S. and Napier, J. 2013. Research Methods in Interpreting: A Practical Resource. New York: Continuum.

Hale, S. and Gonzalez, E. 2017. Teaching legal interpreting at university level: A research-based approach. In: Cirillo, L. and Niemants, N. eds. Teaching Dialogue Interpreting Research-based proposals for higher education. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp.199-216.

Hale, S., Ozolins, U. and Stern, L. 2009. The critical link 5: quality in interpreting: a shared responsibility. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hancock, A.-M. 2007. When Multiplication Doesn’t Equal Quick Addition: Examining Intersectionality as a Research Paradigm. Perspectives on politics. 5(1), pp.63–79.

Hardman, I. 2023. Fighting for Life: The Twelve Battles That Made Our NHS, and the Struggle for Its Future. London: Viking.

Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hayek, F. A. 1944. The Road to Serfdom. Routledge.

Healy, G. 2016. The Politics of Equality and Diversity: History, Society, and Biography. In: Bendl, R. and Bleijenbergh, I. and Mills, A. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Diversity in Organizations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Healy, G. and Oikelome, F. 2013. Diversity, Ethnicity, Migration and Work: International Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Heery, E. and Simms, M. 2010. Employer responses to union organising: patterns and effects. Human Resource Management Journal. 20(1), pp.3–22.

Hick, R. and Lanau, A. 2017. In-work poverty in the UK: problem, policy analysis and platform for action. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

Hills, J., Brewer, M., Jenkins, S. P., Lister, R., Lupton, R., Machin, S. and Riddell, S. 2010. An anatomy of economic inequality in the UK. Report of the National Equality Panel. Accessed 2 December 2024. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/28344/1/CASEreport60.pdf

Himmelfarb, G. 1974. On Liberty and Liberalism: The Case of John Stuart Mill. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hirsch, D. 2013. Addressing the poverty premium: approaches to regulation. London: Consumer Futures.

Hlavac, J. and Commons, J. 2023. Profiling today’s and tomorrow’s interpreters: Previous occupational experiences, levels of work and motivations. The international journal of translation and interpreting research. 15(1), pp.22–44.

Hobbes, T. 1651. Leviathan. England: Andrew Crooke.

Honig, B. 1995. Women, the Family, and Utopia: A Theory of Feminist Criticism of Political Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

House of Lords, 2023. Victims and Prisoners Bill. Accessed 19 August 2024. https://www.parallelparliament.co.uk/lord/baroness-coussins2/debate/2023-12-18/lords/lords-chamber/victims-and-prisoners-bill

House of Lords, 2024a. Inquiry: Interpreting and translation services in the courts. https://committees.parliament.uk/work/8493/interpreting-and-translation-services-in-the-courts/

House of Lords, 2024b. Public Services Committee’s Event on Wednesday 18 December 2024. Accessed 5 January 2025. https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/2ae08a79-616b-419b-8d9c-5a769831e5f5