By Fardous Bahbouh, Researcher & Consultant on Labour Rights, Public Policy, and the Political Economy of the Translation Industry

Dear Baroness Morris,

I hope this message finds you well. I want to express my deep gratitude for your considerable efforts in leading the House of Lords inquiry into court interpreting—I greatly appreciate it.

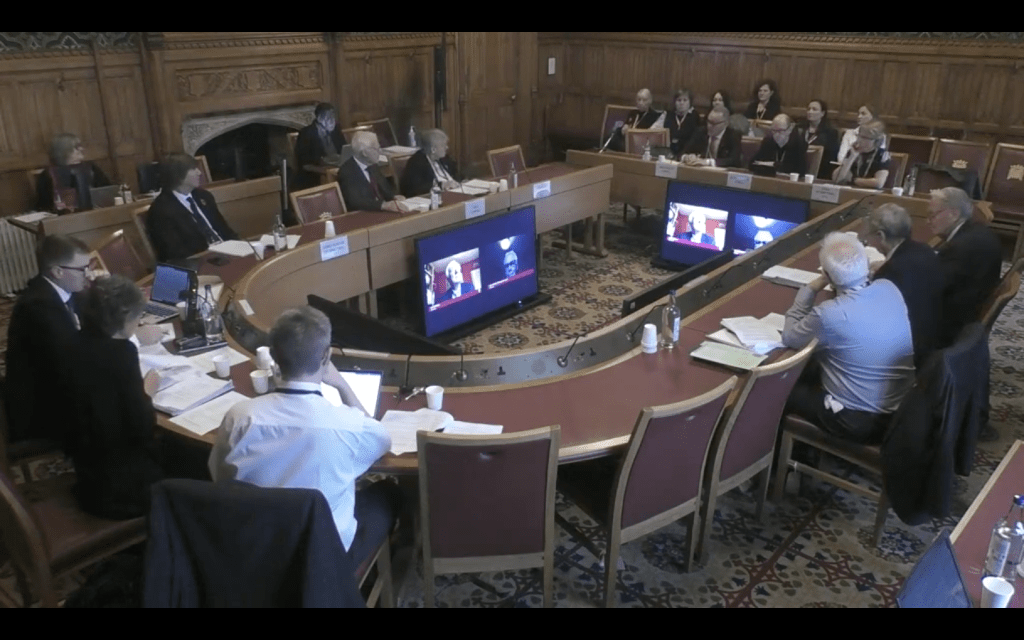

I am writing to convey my serious concerns about the lack of interpreters’ representation in the recent sessions. I hope that at some point, your committee will hear directly from interpreters, rather than simply “displaying” them. It was disheartening to watch yesterday’s session, especially with interpreters seated at the back while non-interpreter CEOs -none of whom has lived experience of precarious work- spoke on their behalf.

I sincerely urge the committee to incorporate an intersectional framework to address complex, intersecting inequalities, lack of meaningful representation, and underlying power dynamics. Interpreters in the UK are predominantly from migrant backgrounds and mostly women—95% of interpreters registered with the National Register for Public Service Interpreters (NRPSI) identify English as their second language, and 64% are women (NRPSI, 2018). It was truly upsetting with too much “whiteness in the conversations” while interpreters’ insights and testimonies were missing.

While Sara began well by acknowledging interpreters’ low pay and challenging work conditions, I found it disheartening that she concluded with a focus on interpreters leaving the profession—as if interpreters only matter when they are working [and paying membership and training fees], rather than as valued members of our society. I wish she had elaborated on how these conditions affect interpreters’ quality of life, including financial insecurity, loss of control over their time, stress, and even deteriorating health. These factors significantly impact interpreters’ well-being and job satisfaction [in addition to reproductive injustices and child poverty]. In addition to immediate financial strain, interpreters face long-term career challenges, as the current system restricts their opportunities for skill-building and relevant experience, which limits upward mobility. Doesn’t Mike see an issue with interpreters leaving court interpreting to work in bakeries?

For many interpreters, living “pretty much on the poverty line” is a reality. It was striking that terms like “exploitation,” “marginalisation,” and “oppression” were left unspoken, even though they capture the reality of the situation. [Though we should give them credit for the visual demonstration of the marginalisation of interpreters. It was very powerful!]

It’s also essential to recognize that not everyone can afford to leave the profession, especially those with caregiving responsibilities or those who have invested significant time and resources in qualifications, being promoted by these CEOs. Many interpreters may remain in exploitative arrangements due to a lack of viable alternatives, compounded by structural inequalities and intersectional barriers (Huws, 2014; Warren and Lyonette, 2015). For instance, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) reported that by 2022, 3.9 million people in the UK were in insecure employment, including zero-hour contracts, low-paid jobs, and temporary agency work.

It was also concerning to hear John propose a rate of £30. Does he truly believe that interpreters can make a living on sporadic assignments at that rate? I was thankful to Lord Carter for asking “How much does an interpreter make a year?”—as it was apparent that none of the three representatives had a clue. I’ve reached out multiple times to these organisations, raising concerns and offering support to help them become more inclusive and representative, but my efforts have been in vain.

For context, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation stated in 2023 that a single person would need to earn £29,500 annually to meet a minimum acceptable living standard, while a couple with two children would need £50,000 between them (2023, p. 2). Before advocating for diplomas and registration fees, it would be prudent for these organizations to evaluate how many interpreters actually earn a living wage.

John’s comments also seemed to represent translation companies rather than interpreters, particularly when discussing concerns about “pipelines” [into exploitive outsourcing] —or was he referring to a steady stream of linguists paying for memberships and diplomas his institute offers? There are many ethical issues here. Such diplomas rarely yield a financial return or lead to more stable jobs or improved working conditions, as I mentioned in my written evidence to the committee. Is it not ethically problematic that these organisations continue to promote them?[Ironically, in their written evidence, the CIOL demanded a pay rise for the translation company holding the Ministry of Justice contract, expecting the company’s generosity to trickle down and result in better pay for interpreters. It’s an absurd idea that all those CEOs, in collaboration with the interest group representing translation companies (ATC), agreed on in 2023.]

While the three CEOs supported a national register for quality control, they failed to address the unfairness of requiring interpreters to cover the cost, given how underpaid and undervalued they are. Shouldn’t the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) be responsible for quality control? Do civil servants in the UK pay for their own professional development and background checks? Why, then, should interpreters have to bear these costs themselves? Isn’t it strange that the very “CEOs” supposedly representing interpreters are advocating for this? The NRPSI is simply a legacy institute, and even Mike himself acknowledged how ineffective it is. [Why doesn’t Mike apply for a grant or a contract from the MoJ if he wants to act as a regulator or a quality controller??? NRPSI is charging each interpreter £252 annually, yet he still refuses to prioritise advocacy for interpreters or even listening to them! Isn’t this ethically problematic? Personally, I see this as an added layer of oppression, where outsourcing leads to the exploitation of interpreters and the devaluation of their skills and expertise. And on top of that, Mike wants to charge them fees so he can act as a “police officer” catching the “baddies.” And yes, I do wonder if the fact that interpreters are predominantly from minority ethnic backgrounds, and mostly women, has something to do with this power imbalance].

Thank you very much for your time and consideration. I previously reached out to express my concern that the inquiry’s announcement was only in English, potentially excluding service users with limited English proficiency. I hadn’t anticipated that interpreters themselves would also be sidelined in such a disheartening way. I’m sure you’d agree this does not align with the standards we aspire to uphold as a nation [and it is not in the interest of justice].

Kindest regards,

Fardous

Here is a link to the panel. Just a disclaimer that it is not really pleasant to watch if you are equality oriented. I was pulling my hair! [I later added the notes in brackets to this post for clarity.]

References:

Huws, U. 2014. Labor in the Global Digital Economy: The Cybertariat Comes of Age. Monthly Review Press.

NRPSI. 2018. NRPSI Annual Review of Public Service Interpreting in the UK. 6th Edition. Accessed 1 January 2024. https://www.nrpsi.org.uk/downloads/1240_NRPSI_Annual_Review_6th_Edition.pdf

NRPSI. 2023. Fees. Accessed 28 August 2024. https://www.nrpsi.org.uk/for-interpreters/fees.html

Joseph Rowntree Foundation. 2023. A Minimum Income Standard for the United Kingdom in 2023. Accessed 25 August 2024. https://www.jrf.org.uk/a-minimum-income-standard-for-the-united-kingdom-in-2023

Trade Union Congress. 2023. Insecure work in 2023. Accessed 23 October 2024. https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/insecure-work-2023

Warren, T. and Lyonette, C. 2015. The quality of part-time work. In: Felstead, A., Gallie, D. and Green, F. (eds) Unequal Britain at work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leave a comment