By: Fardous Bahbouh, Researcher & Consultant on Labour Rights, Public Policy, and the Political Economy of the Translation Industry

On 15 September 2017, I attended the Diversity in Media Awards at the Waldorf Hilton. My teacher at the London College of Communication, Vivienne Francis, had been nominated for an award, and I was there to celebrate her incredible achievement. Among the attendees were many familiar faces, including Lily Allen, who spoke passionately about the Grenfell Tower tragedy—a tragedy that could have been avoided if those in power had cared enough. But when Diane Abbott was named Icon of the Year, I could not stomach it.

I did not want to make a scene, but later walked over to her table and politely asked, “Since you are winning an award for promoting diversity, why wouldn’t you listen to Syrians?” She gave me a disdainful look and murmured something about not knowing what I was talking about.

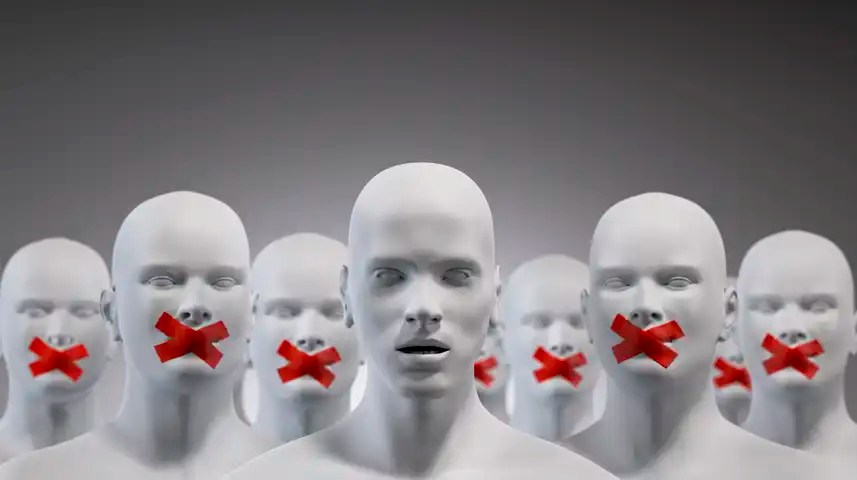

The background story, as shown in the BBC video below, was that Bashar al-Assad had been killing and gassing thousands of Syrians for years. Yet Diane Abbott hosted an event at the British Parliament, organised by the Stop the War Coalition, about Syria—where no Syrians were invited to speak. Even when Syrians in the audience tried to speak up, they were not allowed to contribute from the floor. You can see in the video how the activist Peter Tatchell spoke out in frustration at this exclusion.

It is unbelievable that she did that. But to be fair, Diane Abbott was not the only one who refused to listen to Syrians. Many politicians and so-called pundits insisted on a narrative that reduced the revolution to a Western conspiracy for regime change. Acknowledging it as a genuine revolution would have required recognising Syrians as agents of their own destiny—people capable of independent action, fighting for their own dignity, freedom, and future. But that recognition was denied to them. It was tragic, offensive, and extremely ignorant.

At the awards party, I could not remain silent. The images of torture and mass killings that I had been witnessing from afar came rushing back. I was used to spending endless hours scrolling through my Facebook feed, anxiously checking on family, friends, and former colleagues and students from all over Syria. Before the revolution, I had spent two years teaching at a university there. It was really painful to watch, from a distance, as their lives unraveled in real-time.

I still respected Diane Abbott as a Black woman in politics. I wished we had more women, especially women from BAME backgrounds, in politics. However, I was deeply upset to see the same woman who had first-hand experience of the harm of hate and marginalisation doing the same to others. I still do not understand how that was possible, and it was infuriating to see her win a diversity award. By refusing to listen to Syrians about what was happening in their own country and imposing a Western lens that dismissed their voices, she was reproducing a colonial framework—one where she felt entitled to let her perspective take precedence over Syrian realities.

I am remembering this now because, finally, Syria is free, and because I still meet people, even from migrant or minority ethnic backgrounds, who also silence others and impose their views. Diversity cannot be about selective inclusion. Decolonising the narrative means amplifying the voices of those directly affected rather than speaking for them or speaking at them.

That night, I was not looking for an argument—I simply wanted the newly crowned diversity champion to know that Syrians deserved to be heard about their own struggle. Similarly, when I speak about decolonising the narrative now, it is not for the sake of debate but because I genuinely believe in its necessity.

Leave a comment